Lunch with the Twins, 2014

Curated by Avi Ifergan

Kabri Gallery

A Conversation between Ravid Rovner, Avi Ifergan and Yaron Attar.

Ravid Rovner: This discussion is framed as a question – 'Why did the painter kill the editor?' The question is, of course, directed at the painting Death of the Editor, but it also suggests a key to understanding the entire exhibition. Let’s conduct a methodical analysis of the aesthetic, thematic, and curatorial elements to first understand the question, and only then attempt to answer it. Perhaps, through this process, we will also grasp the meaning behind the exhibition’s title – Lunch with the Twins.

R.R: What is the connection between Death of the Editor and Roland Barthes' Death of the Author? Barthes argued that the author is 'dead' because every reader has the right to interpret a work based on their own understanding, regardless of the author's intention. When you speak of Death of the Editor, how is it different?

Yaron Attar: Death of the Editor considers the phase that follows Death of the Author. The painting expresses a desire to take the postmodern trajectory to its extreme or perhaps even to its end. The editor, responsible for cutting, pasting, manipulation, and deconstruction—whether in text, film, or video—is the one who ultimately determines the structure, sequence, and rhythm of a work. The editor’s death signals a new era where everything is presented without manipulation, appearing as a singular, unaltered whole.

R.R: Many of your paintings convey a sense of time frozen, as if depicting situations that do not progress. Except for Death of the Editor, where the figure appears to be drawn into a black hole, just moments before detaching from the keyboard. How does this align with the concept of Death of the Editor? If the editor is dead, shouldn’t the film continue running? Yet, in your painting, it feels as though we are looking at still frames taken from a film.

Y.A: My paintings deal with the tension between movement and stasis. Death of the Editor marks a moment of collapse, where the character’s final act—reaching for the editing keyboard—takes on an almost ritualistic significance. If the editor is dead, perhaps control over time and narrative has also vanished. The figure is being pulled into the black hole, but we do not know whether they completely disappear or if the suction itself is infinite, frozen in a moment of transformation. I want the viewer to remain in this tension—does this depict an absolute end, or an ongoing moment?

R.R: The exhibition’s display also conveys a sense of rhythm and calculated order. Can you elaborate on this?

Avi Ifergan: The arrangement of the works in the exhibition was designed with a cinematic viewing experience in mind. The spacing of 24 cm between the works corresponds with the 24 frames per second standard in film, while the total of 30 works creates a sense of motion, like a pause capturing moments from a visual sequence. This layout gives each work individual significance while simultaneously immersing the viewer in a continuous, almost narrative experience, where connections are formed through the very arrangement itself.

R.R: 24 is the number of frames per second in a film. With 30 works, it feels as if we are looking at stills taken from a movie—each one a frozen frame, trapped in a singular moment. Sometimes it’s a distant, photographic gaze (Snow, Bastards), and sometimes a close-up (The Villain, The Fabrics Blowing in the Wind). Was this intentional?

Y.A: The decision for a dense and systematic arrangement creates a sense of overload but also a constant connection between the images. Instead of a classic display that allows for isolated viewing of each piece, this setup mimics cinematic editing—like frames accumulating along a timeline. The gaze cannot settle on a single work; it moves between them, shifting like scenes in a film. This generates a nearly cinematic experience, where the relationships and gaps between the works construct a new narrative."

R.R: Since all the works are aligned on the same line, it creates an image reminiscent of a heartbeat monitor or a seismographic recording.

Y.A: The rhythm and structure of the display play a central role in the exhibition. The continuous arrangement generates a dynamic similar to cinematic movement, while simultaneously fixing the images in a frozen sequence. This manipulation echoes the presence of the editor—even in their absence.

R.R: You are also a video artist. In your video works, you present highly realistic imagery, whereas in your paintings, you use smearing techniques and other effects. How do you perceive this difference?

Y.A: In my video works, I strive to capture reality as it is, without the need for editing. In painting, however, I engage with abstraction and the relationship between control and lack of control—how color and material dictate the emergence of the image through painterly actions like smearing, erasing, and spray paint application.

R.R: You chose to present oil paintings on relatively raw materials rather than traditional canvases. How does this choice relate to the idea of technology and the negation of time?

Y.A: The use of raw materials creates a dialogue with the concept of impermanence and temporality. It emphasizes the disintegration of the image and the fragility of the material itself, challenging traditional painting conventions. The undefined and ever-changing materiality dictates the image, generating tension between the fixed and the dissolving.

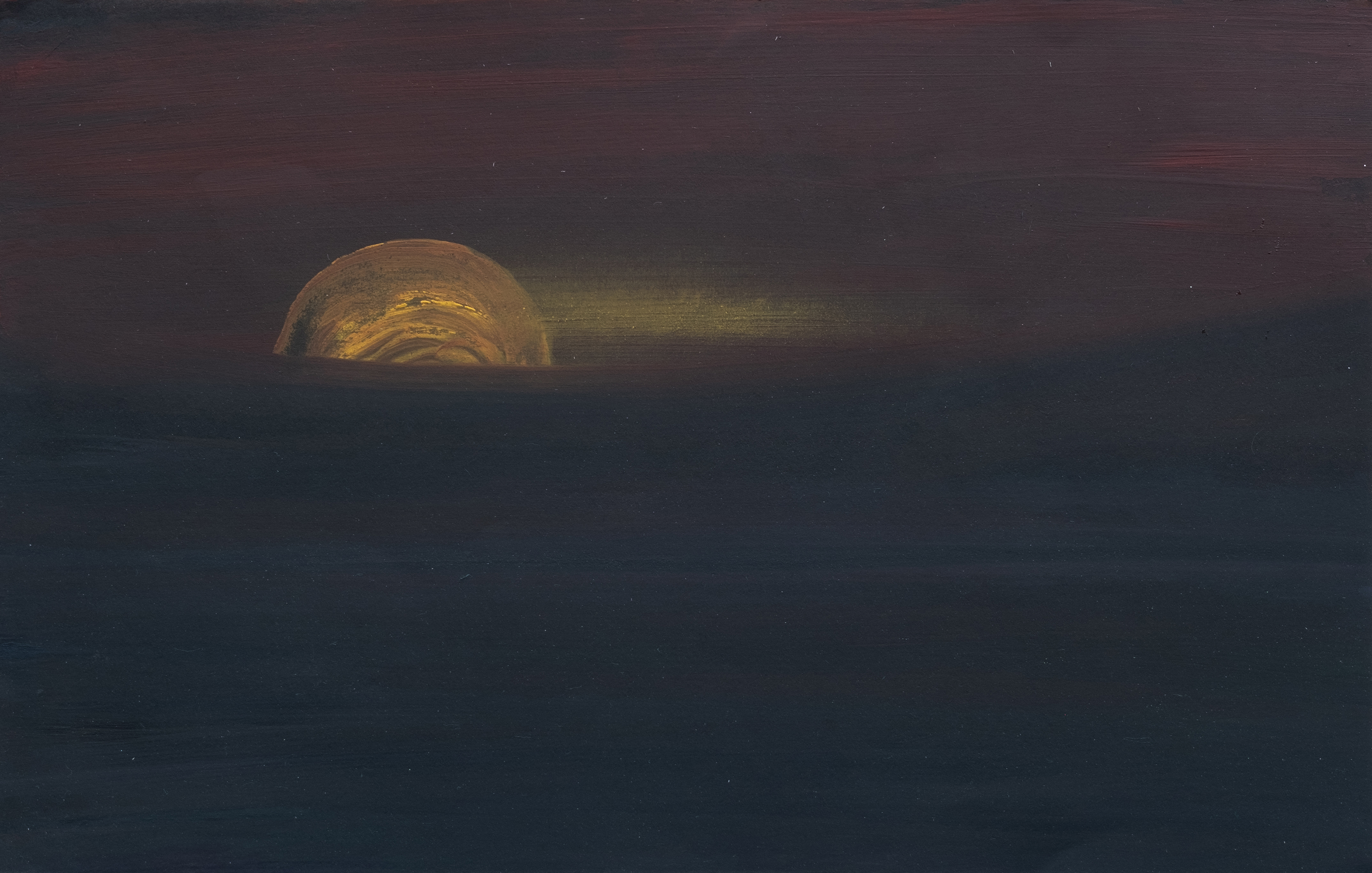

R.R: I noticed that you did not place titles beside the paintings, instead providing a separate list. Looking at this list, a sense of sorrow, death, and farewell emerges: Woman, Death of the Editor, Blood Pact, Eclipsed Sun, The Editor and the Demon, Shark 1, Shark 2, Bank Robbery, Leg Brace, African Sculpture, The Rope, and more.

Y.A: I don’t see this as sorrow but rather as a dynamic stretched between drama and collapse. There is tension building within the paintings, yet it then shatters into moments of abstraction and instability. If there is death, it is not absolute—it is also transformative. The power of painting lies in its ability to simultaneously contain both creation and destruction, and often, both occur at the same moment.

Lunch with the Twins, 2014

Curated by Avi Ifergan, Kabri Gallery

A Conversation between Ravid Rovner, Avi Ifergan and Yaron Attar.

Ravid Rovner: This discussion is framed as a question – 'Why did the painter kill the editor?' The question is, of course, directed at the painting Death of the Editor, but it also suggests a key to understanding the entire exhibition. Let’s conduct a methodical analysis of the aesthetic, thematic, and curatorial elements to first understand the question, and only then attempt to answer it. Perhaps, through this process, we will also grasp the meaning behind the exhibition’s title – Lunch with the Twins.

R.R: What is the connection between Death of the Editor and Roland Barthes' Death of the Author? Barthes argued that the author is 'dead' because every reader has the right to interpret a work based on their own understanding, regardless of the author's intention. When you speak of Death of the Editor, how is it different?

Yaron Attar: Death of the Editor considers the phase that follows Death of the Author. The painting expresses a desire to take the postmodern trajectory to its extreme or perhaps even to its end. The editor, responsible for cutting, pasting, manipulation, and deconstruction—whether in text, film, or video—is the one who ultimately determines the structure, sequence, and rhythm of a work. The editor’s death signals a new era where everything is presented without manipulation, appearing as a singular, unaltered whole.

R.R: Many of your paintings convey a sense of time frozen, as if depicting situations that do not progress. Except for Death of the Editor, where the figure appears to be drawn into a black hole, just moments before detaching from the keyboard. How does this align with the concept of Death of the Editor? If the editor is dead, shouldn’t the film continue running? Yet, in your painting, it feels as though we are looking at still frames taken from a film.

Y.A: My paintings deal with the tension between movement and stasis. Death of the Editor marks a moment of collapse, where the character’s final act—reaching for the editing keyboard—takes on an almost ritualistic significance. If the editor is dead, perhaps control over time and narrative has also vanished. The figure is being pulled into the black hole, but we do not know whether they completely disappear or if the suction itself is infinite, frozen in a moment of transformation. I want the viewer to remain in this tension—does this depict an absolute end, or an ongoing moment?

R.R: The exhibition’s display also conveys a sense of rhythm and calculated order. Can you elaborate on this?

Avi Ifergan: The arrangement of the works in the exhibition was designed with a cinematic viewing experience in mind. The spacing of 24 cm between the works corresponds with the 24 frames per second standard in film, while the total of 30 works creates a sense of motion, like a pause capturing moments from a visual sequence. This layout gives each work individual significance while simultaneously immersing the viewer in a continuous, almost narrative experience, where connections are formed through the very arrangement itself.

R.R: 24 is the number of frames per second in a film. With 30 works, it feels as if we are looking at stills taken from a movie—each one a frozen frame, trapped in a singular moment. Sometimes it’s a distant, photographic gaze (Snow, Bastards), and sometimes a close-up (The Villain, The Fabrics Blowing in the Wind). Was this intentional?

Y.A: The decision for a dense and systematic arrangement creates a sense of overload but also a constant connection between the images. Instead of a classic display that allows for isolated viewing of each piece, this setup mimics cinematic editing—like frames accumulating along a timeline. The gaze cannot settle on a single work; it moves between them, shifting like scenes in a film. This generates a nearly cinematic experience, where the relationships and gaps between the works construct a new narrative."

R.R: Since all the works are aligned on the same line, it creates an image reminiscent of a heartbeat monitor or a seismographic recording.

Y.A: The rhythm and structure of the display play a central role in the exhibition. The continuous arrangement generates a dynamic similar to cinematic movement, while simultaneously fixing the images in a frozen sequence. This manipulation echoes the presence of the editor—even in their absence.

R.R: You are also a video artist. In your video works, you present highly realistic imagery, whereas in your paintings, you use smearing techniques and other effects. How do you perceive this difference?

Y.A: In my video works, I strive to capture reality as it is, without the need for editing. In painting, however, I engage with abstraction and the relationship between control and lack of control—how color and material dictate the emergence of the image through painterly actions like smearing, erasing, and spray paint application.

R.R: You chose to present oil paintings on relatively raw materials rather than traditional canvases. How does this choice relate to the idea of technology and the negation of time?

Y.A: The use of raw materials creates a dialogue with the concept of impermanence and temporality. It emphasizes the disintegration of the image and the fragility of the material itself, challenging traditional painting conventions. The undefined and ever-changing materiality dictates the image, generating tension between the fixed and the dissolving.

R.R: I noticed that you did not place titles beside the paintings, instead providing a separate list. Looking at this list, a sense of sorrow, death, and farewell emerges: Woman, Death of the Editor, Blood Pact, Eclipsed Sun, The Editor and the Demon, Shark 1, Shark 2, Bank Robbery, Leg Brace, African Sculpture, The Rope, and more.

Y.A: I don’t see this as sorrow but rather as a dynamic stretched between drama and collapse. There is tension building within the paintings, yet it then shatters into moments of abstraction and instability. If there is death, it is not absolute—it is also transformative. The power of painting lies in its ability to simultaneously contain both creation and destruction, and often, both occur at the same moment.